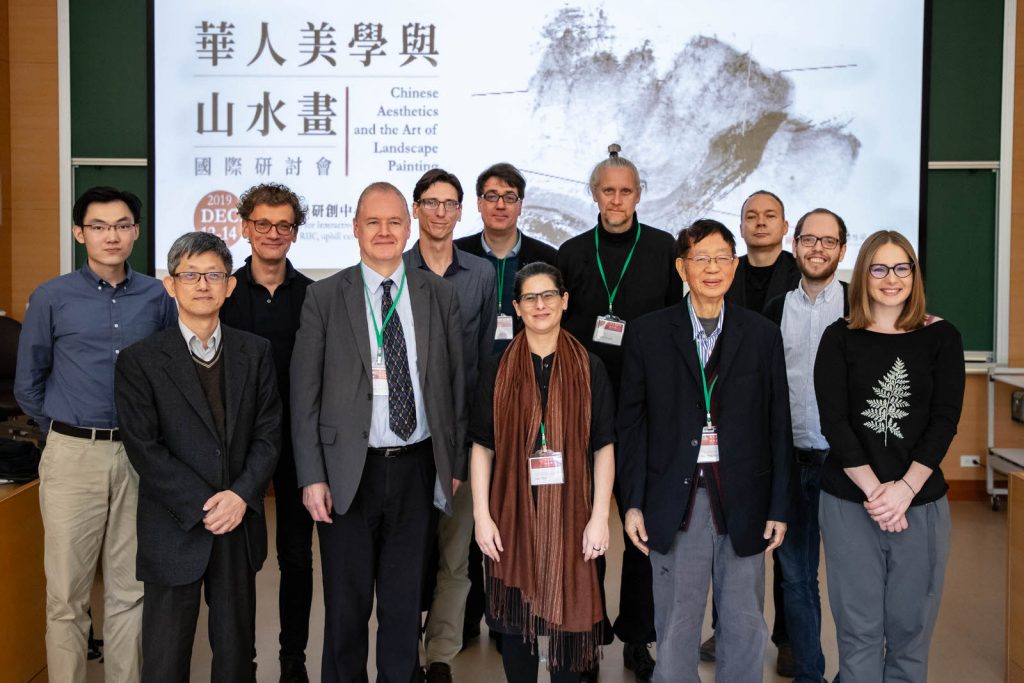

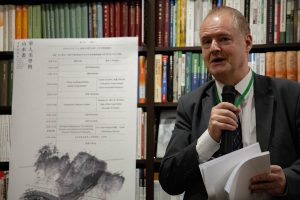

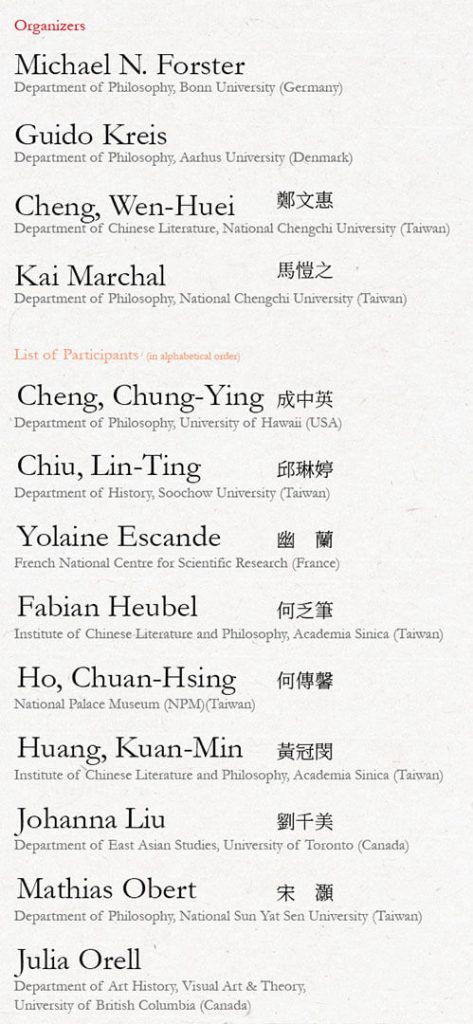

華人美學與山水畫 國際研討會

Chinese Aesthetics and the Art of Landscape Painting

日期Date

12/12/2019(Thu)

|

12/14/2019(Sat)

語言Language

English&Manderin

地點Venue

南天書局(台北市羅斯福路三段283巷14弄14號)

國立政治大學研創中心1樓 互動式講堂Teaching Lab for Interactive Learning, RIIC, uphill campus of National Chengchi University(NCCU)

- 國立政治大學華人文化主體性研究中心 / Research Center for Chinese Cultural Subjectivity in Taiwan, NCCU

- 德國波昂大學 / Bonn University, Germany

會議舉辦緣起

傳統中國山水畫一直以來都是中國藝術中的典範代表,而中國文人理想脈絡中的藝術活動又緊密與涉及群山、樹木、川河、竹林、涼亭等今日會直接標示為山水畫關鍵特徵的繪畫創作上。若我們要重建任何審美傳統與理論的論述,絕對不可缺少的便是臨現當前且具體的美感體驗。與其僅僅概括且高度抽象地以談論美感理論為出發點,本研討會另闢蹊徑,以實際體驗中國山水畫的體驗,作為「概念取徑」與「個殊華人處境下而發展的向度」這兩造之間對話活動的鋪陳,進而探索活生生藝術體驗與觀點交錯的可能性。

本研討會所邀請發表論文的面向因而可綜述如下:

- 山水畫的文法向度(the Grammar of a Painting)

- 山水畫的世界( the World of a Painting)

- 山水畫的神韻所在( the Spirit of a Painting)

- 就其脈絡來談山水畫 ( Paintings in their Contexts)

- 理論視角裡的山水畫 ( Paintings in Theory)

- 山水畫與華人美學( Landscape Paintings and Chinese Aesthetics)

- 美學: 東方與西方的取徑比較 ( Aesthetics- East and West)

About

Traditional Chinese landscape painting is a paradigmatic genre of Chinese art. The “Chinese literati ideal” of artistic production is closely associated with the painting of mountains, rivers, trees, bamboo, pavilions and other elements of what we today simply call landscapes. We presume that the reconstruction of any aesthetic tradition and theory always requires actual aesthetic experience on the spot. Instead of merely discussing aesthetic theorems in a general and highly abstract way, we want to take the experience of actual Chinese landscape paintings as a starting point for further discussion. We thus hope to foster a dialogue between more conceptually driven approaches to Chinese art and more specialized, sinological ones.

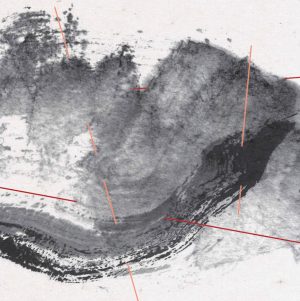

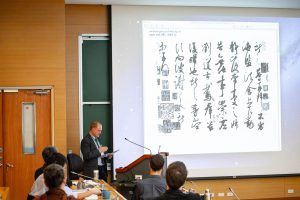

Asking how Chinese landscape paintings are made leads to a discussion of their

technique and grammar, including all kinds of material aspects. We observe a rich variety of brushstrokes in the paintings: for instance, axe-cut strokes, long and short hemp fiber strokes, and cloud head strokes. The paintings work with different kinds of textures (rough, soft, etc.), contrasts (created by light and dark ink), outline patterns, repetitive shapes, dots, etc. Case-studies of individual painters can demonstrate how the standard vocabulary of brushstrokes is relevant for individual style (fengge 風格). The paintings rely on methods of using brush and ink developed in the practice of calligraphy, so how do calligraphy and painting relate?

How do landscape paintings create what we might call their world? In what ways do they achieve the impression of a richly structured and accentuated nature in which human beings with their dwellings, cultural achievements, and social life make their appearance?

How does the world created in the paintings relate to reality? Is it purely imaginative and‘fictional’, or does it represent and depict (features of) the actual world? Is the relation between the world of a painting and the actual world as such thematized, and is the awareness of this difference relevant for aesthetic experience?

Is there anything like the spirit of a painting, and if so, how can it best be characterized? For example, is the landscape depicted in a painting a vehicle for expression? Are personally expressive styles relevant, or is the painting more about a trans-individual spirit of a landscape? Do paintings express general ideas, like the harmony of existence, or the order of the universe? What is the role of qi 氣, i.e. “animating spirit” or “energy”? Similarly, are the recipients supposed to draw suitable lessons from their aesthetic

experience, e.g., are they invited to pattern their social existence in accordance with

these ideas? Or do paintings express a spirit that is not fully accessible and hence remains essentially inexplicable? Also, how to understand the notion of beauty correlated to individual landscape paintings?

How are the paintings situated in different social and religious contexts, and how do

these contribute to the actual shape of the paintings, and prefigure and guide special

ways of aesthetic experience? Is it possible to (appropriately) experience the paintings outside these particular historical contexts? Is there any idea of the autonomy of art in general, and landscape paintings in particular?

How is landscape painting reflected in the classical literature, in particular in the treatises on landscape painting? In those cases where the texts go beyond the aims and intentions of instruction manuals and develop (bits of) aesthetic theory in their own right, how do theory and practice then relate to each other? What are the relevant categories by help of which the paintings are characterized? Does theory come before, or only after the actual practice of painting? Does theory prescribe how to produce and experience actual paintings? How to understand, f.ex., Jing Hao’s 荆浩 reflections on the “real sight” (zhen jing 真景) or Su Dongpo’s 蘇東坡 notion of “so-of-itself” (ziran 自然)? And are comparisons with European theory and art history (say the notion of mimesis or Petrarca’s“discovery of landscape”) useful at all or do they necessarily strengthen stereotypes about some other culture’s art and should thus rather be avoided?

What can the paradigm of classic Chinese landscape painting tell us about Chinese

aesthetics more generally? How do the categories developed in the characterization of landscape painting relate to Chinese literature and music, to other genres of art, and to Chinese aesthetics more broadly construed?

What can we learn from Chinese landscape painting for the problem of comparative

aesthetics East and West? Is there a specifically Chinese approach to art, nature, and

culture? In what ways might Western aesthetics be constructively challenged by Chinese aesthetics? How might a truly globalized art history change the currently available conceptual schemes for analyzing aesthetic experience?

The goal of our conference will be to re-think some of these questions by taking concrete aesthetic experiences as point of departure for theoretical reflections.